*Positioning

How does positioning work in your market?

Positioning. In practice, we repeatedly find that everyone has a different idea about positioning. This is particularly challenging when you’re trying to persuade the organization to reconsider your brand’s positioning but ‘they’ don’t see the need for it. That’s why in this article, we’ll take a closer look at the bigger picture surrounding the question: Positioning in the market, how does it actually work? We will also discuss how to get your colleagues or management moving in the right direction.

Origin of positioning

The verb “positioning” actually only came into existence in the 1970s. Jack Trout wrote an article for the trade journal ‘Industrial Marketing’ titled “Positioning is a game people play in today’s me-too market place.” In this article, he wrote that consumers are bombarded with advertising messages and simply ignore them unless they immediately find an easy (and free) place in their minds. This thinking about finding an easy and free place was further developed with Al Ries into the book “Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind” in 1981.

Positioning continued to evolve, and today, we define it as follows:

“To connect a set of characteristics and properties to a product [or service] in such a way that it obtains its own place in the mind of the customer in comparison to competitive products [or services].”

Positioning consists of three factors: the perception of the brand by the target audience or customer, the identity of the brand, and the desired positioning. What makes positioning so interesting is the influence these three elements have on each other and on the positioning. This is easiest to explain with an example.

Practical example: Positioning in the industrial market

We’ll assume a completely fictitious market and players, but in a situation we often encounter in practice:

Alpha Industrial has been in business for 40 years, supplying heating elements to installers and contractors. The company only sells through wholesalers and has been the market leader for years with a 40% market share. It uses the slogan “Reliability and top quality” and occasionally exhibits at two trade shows and places advertisements in industry magazines from time to time. Competitors Beta Heating and Gamma Warmth have 25% and 15% market share, respectively. The remaining 20% is divided among several smaller players. Both Beta and Gamma follow a me-too marketing strategy and effectively mimic Alpha’s marketing.

Two years ago, a new player entered the market: Omega Production. In a short time, market challenger Omega managed to gain a 20% market share, partly due to the slogan “Good and cheaper.” Omega produces much more cheaply in China, which is reflected in the selling price. They also invest heavily in marketing, and the target audience can’t ignore them. Alpha is now at a loss, seeing a 10% market share vanish in 2 years, and margins have been greatly reduced due to increased price pressure. While they attributed the decline to “the market” in the first year, they made every effort to reverse the tide in the second year. All in vain.

The positioning problem

The above situation may have many similarities to your market. It’s a situation we encounter all too often, in any case. Using the factors perception, identity, and desired positioning, we can show where things went wrong.

Perception – The target audience had made their choice years ago, and since the three brands remained the same, they never really had to choose. Most opted for Alpha and were willing to pay a little more for peace of mind, while others chose the somewhat friendlier numbers two or three. Now Omega appears with a product that is 40% cheaper but of sufficient quality, and finally, the target audience has something to choose from, and they do.

Identity – Alpha’s identity is tied to only one thing: market leadership. Beta and Gamma follow Alpha’s themes and talk about quality and reliability as well. If you were to ask them, none of the three could tell you exactly what sets them apart from the rest. The problem is that they don’t make the right decisions as a result. Omega? They want to be ‘Cheaper and practically just as good’ and invest in efficiency under the assumption that being cheaper will lead to more market share.

Desired positioning – I think this is clear by now. Alpha wants to keep things as they are, maybe a little more prestige and market share, but otherwise, things are fine. Beta and Gamma simply want to steal market share from each other and Alpha, and possibly take the lead. None of the three thinks about changing course because “that’s just the way the market works.” Omega captures 20%, and panic sets in, while none of the three has a positioning to hold onto.

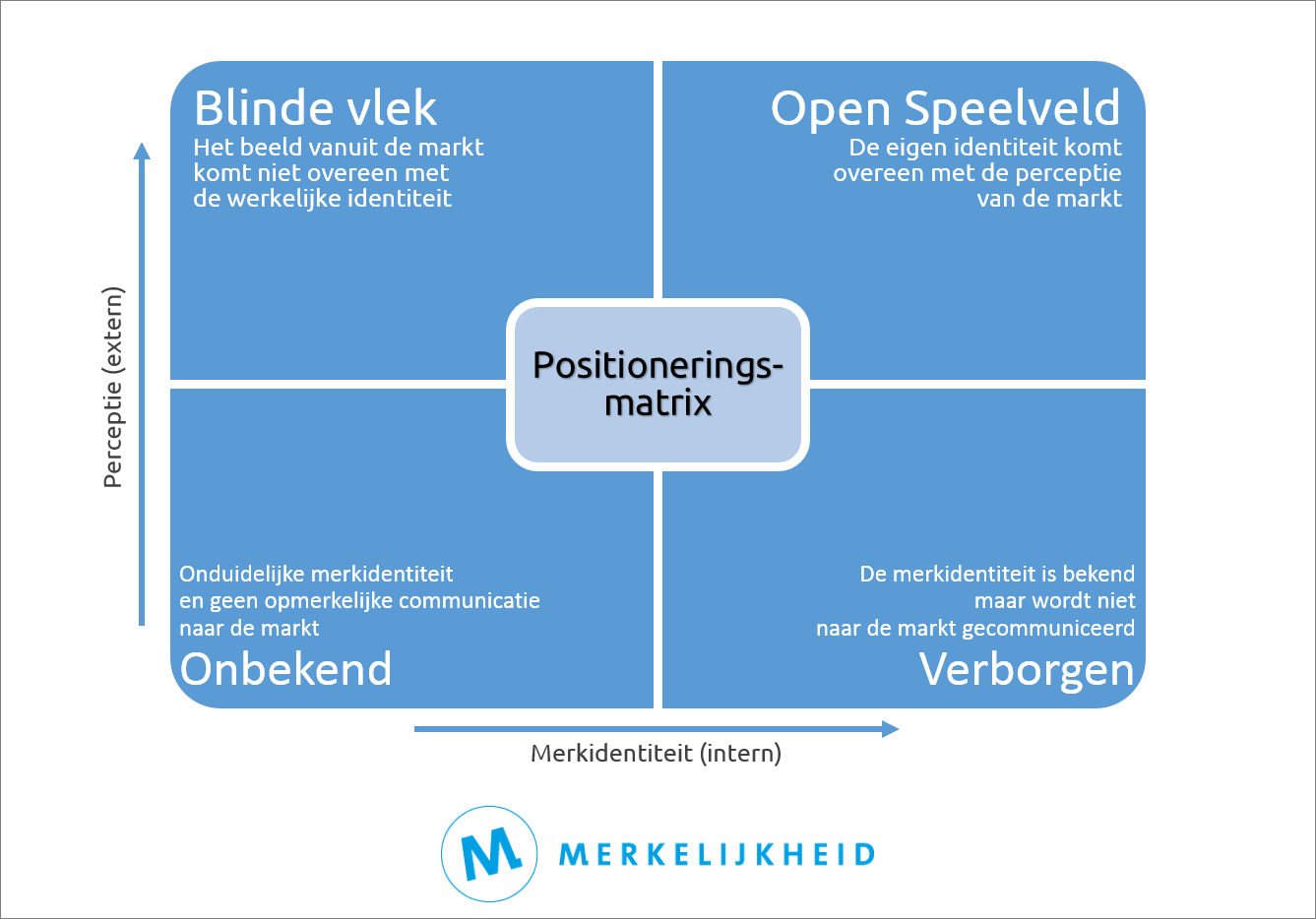

The positioningsmatrix

Issues like these arose so frequently that we developed a model for it: the positioning matrix. In the positioning matrix, you plot perception against identity to determine whether the challenge exists or if you fall into an “open playing field.” The open playing field is a situation where you precisely know what your identity is while the market recognizes and values it, meaning you are distinguishable from the competition. In the other three quadrants, you face a challenge:

1. Blind Spot: The brand has its “eyes closed” and completely lacks a sense of the market, while the market can still distinguish the brand from others.

2. Hidden: The brand knows exactly what sets it apart but is unable to convey this to the market effectively.

3. Unknown: Both the market and the brand have no clue, and the brand is literally a “gray mouse.”

By using this model to make the challenges a brand faces clear, we arrive at what matters in practice: positioning.

How does positioning work?

For a brand that wants to position itself as more distinctive in the market, this is usually not an end in itself. It’s often a building block for achieving a business objective such as gaining a larger market share, higher profitability, or increasing competitiveness. Why is this relevant? Because these business objectives strongly determine which positioning you ultimately choose.

By mapping both the brand and the market and keeping the objectives in mind, you can use the positioning matrix to ensure that your team knows precisely where your challenge lies. This gives you the perspective to position the brand optimally in the market and make the right choices. There are various models you can use for the follow-up steps, and we cover many of them in Positioning Models: Which One to Use.

If there’s one thing to take away from this article, let it be that positioning doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Your positioning is partly determined and influenced by factors such as market conditions, target audience, and competition. Instead of resisting this, it’s time to embrace this fact and turn it to your advantage. Develop a positioning framework that outlines all the essential factors and influences for your market, and use this to develop the optimal positioning for your brand. Then, use this same framework to evaluate all your efforts, and you’ll see that you can respond to circumstances much faster and more effectively.

Make sure that when your “Omega” appears, you don’t need two years of discussions before taking action. If you want to learn more about positioning and how to work on it yourself, read our Positioning page. In addition to in-depth articles, you’ll find dozens of examples and models for every possible positioning challenge.